meganbaxter

Remember how I've been lamenting my lack of getting American humour? How British humour makes me giggle, but American humour seems to leave me relatively cold? I take it back. I just haven't been reading good enough American humour, if this book is anything to go by. This book had exactly the tone that makes me laugh. You can ask my husband if I've ever giggled more while reading next to him in the living room. I'd be surprised. Sorry, American humour. It is you, unless it's Jenny Lawson. Apparently.

It is very hard to describe this book, other than hilarious. Sometimes the content is horrifying, often it's describing excruciatingly awkward situations. But damn it, it's funny about all of them! I have a soft spot for women who swear this much. It's part of what I liked about Julie and Julia. I identify with foulmouthed women. The hilarity is an amazing side effect.

Why? I don't know. Maybe I'm emotionally still ten. Maybe I just respond to that honesty of swearing a mile a minute when it's appropriate. You know what? Fuck it. I just like swearing.

Lawson apparently had a strange and sometimes traumatizing but not necessarily horrifying childhood, although I can see how some people might perceive it that way. But there's such affection in this book, and love for those strange moments that might have resulted in a need for therapy. We're all fucked up. Sometimes, we can celebrate how we got there.

Also, a raccoon in jammies? Eeeee!

It's of particular note how Lawson writes about mental health issues, and manages to make it very damn funny indeed, while never underplaying or dismissing it. It rings very true, and the ludicrous note that creeps in doesn't undermine how difficult life can be.

Let's see, what else. It may tell you more about me than anything else that when I was telling him Lawson's stories about starting to collect very strange taxidermied animals, my husband's first reaction was to look me in the eye and say very firmly, "No!"

Even when I told him about the little alligator dressed as a pirate. Which, come on! Who wouldn't want that?

He's no fun sometimes.

Look, I don't know if you'll like this. What strikes me as possibly the funniest book I've ever read may not strike you the same way. But try it anyway. What have you got to lose? At worst, you'll have read about getting your arm stuck in a cow, strange taxidermy, and social anxiety. There's no downside, right?

But I giggled my ass off all the way through this book, sometimes accompanied by gasps. I hope you do the same.

4

4

So, where are the dragons? No, seriously, where are my dragons?

(I really hope everyone has read my review for Tooth and Claw, which I wrote recently, and so have on my mind. Otherwise, that first sentence will seem rather opaque.)

I'm getting very close to having read all of Jane Austen's books. I think I just have Mansfield Park left, unless there's one I'm forgetting. It took me a long time to come to then, perhaps in stubborn response to my younger sisters' enthusiasm for her. I had a comic book adaptation of Pride and Prejudice when I was younger, but that was about it.

The question is, do I have anything new to say about Sense and Sensibility? I'm late chiming in on this, on the order of centuries. I don't feel like the themes created any particularly original thoughts in my head so I guess we'll go with impressions.

I'd seen the Emma Thompson movie version, but from disdainful commentary from someone I work with, I knew that the two weren't that similar. Indeed, I think I was most struck by how far Elinor goes to the side of sense. I knew Marianne was going to be over the top in her desire for true emotion, but Elinor is equally as extreme in her reactions the other way. I wanted to shake her, sometimes, and remind her that while propriety might be good, too much can eat you up inside! If things hadn't turned out the way they had, I could easily see her becoming an embittered old woman.

It is the story of two sisters who take extremely opposite views in how they should behave in society. Elinor is hung up on propriety, and while she's mostly shown to be correct in her choices, she does also use that as an excuse to repress her feelings from everyone, even those to whom she should go for solace. There are times that I worry about her marriage. Will she ever tell her husband if there's something wrong? Or would that be improper?

Marianne, on the flip side, thinks there is something immoral in hiding all emotions, ever. Disagreeing with her on matters of taste is also just plain wrong. She spurns a steady older love interest in favour of a dashing young man who knows exactly what to say to sweep her off her feet.

Elinor and Marianne's joint romantic problems - Marianne in being too attached to someone who doesn't return the emotion, and Elinor in being attached to someone who is not free to pursue her - form the basis of this novel. Marianne learns to be more like her sister, while Elinor's patient silence is rewarded.

Austen is amazingly good at creating characters you would like to strangle, if you could convince them to manifest themselves in front of you for just a minute. And there are those aplenty. The brother, his wife, a few other characters. I was surprised how much I ended up liking Mrs. Jennings, who is silly and jumps to conclusions, but in the end, is a true-hearted friend.

What else is there to say? Late as I came to her works, I always enjoy Jane Austen, although sometimes I want to strangle some of her characters. I'm pretty sure they're the characters I'm supposed to want to strangle, though, so I'm okay with that.

When I first read the description of this book I was skeptical. And perhaps suspicious. Definitely intrigued. This attempts to rectify the main problem of Victorian novels, namely, the lack of dragons. Your reaction is probably fairly similar to mine. Victorian novel...with dragons? Well, I have to say that I was entirely won over, and came out of the book wondering why no one had ever put those obviously needed dragons into a Victorian novel before. (I was reading this at the same time as Sense and Sensibility, and trust me, that made for a weird mix.)

Are you wondering whether or not I have lost my sanity? Well, I'm extremely low on sleep, and yesterday put one of my sisters on a plane for New Zealand, where she is going to live, so there is that. But I finished this book a few days ago, before the insomnia and emotional leavetakings, so I think I'll stand by it. Jo Walton makes this work, dammit. And I enjoyed it quite a bit more than Among Others, with which I had some issues.

It really is weird how well this works, and I think it does so because Walton has such a keen grasp of those issues at the core of many Victorian novels, and manages to translate them quite brilliantly into a society of dragons. Quarrels over inheritance involve both dragon hordes and whether or not the body of the deceased counts as part of the treasure. The cult of true womanhood and the importance of virginity is vividly portrayed by the tendency of these female dragons to turn pink when they are affianced. Or at least, turned on. And it can't be undone, creating a visible sign of honest affianced love, or disgraceful wantonness. (Or can it?) The exploitation of the poor comes to life when dragon lords literally eat the dragonets of the poor, for their own health.

All of these are deftly explored. The underlying metaphors are so solid that this book sucked me in entirely. It's not done with an anvil, but they are slowly elucidated, and knowing Victorian novels, things fall into entertaining place without needing overly complicated explanations. Just like Buffy uses monsters as metaphors to explore teenage issues, Walton uses dragons to tease out certain aspects of Victorian society and explore about them without needing to talk down to her readers.

The grand old dragon, Bon Agornin, has died. His will states that his three youngest children share his treasure, with his older children and the aristocratic mate of his oldest daughter, taking only a token piece of gold for their part. The aristocratic bully does not consider this to apply to the body of his father-in-law and proceeds to devour most of it, depriving the three youngest of their rightful share, and thereby, their future growth. (Dragons depend on eating other dragons to grow bigger.)

The son so deprived launches a lawsuit against his brother-in-law, sundering the family. The other brother, a cleric, does not want to be called to give evidence in the trial, due to some ecclesiastical irregularities about his father's last few minutes. One of the two unmarried daughters is accosted by another cleric, causing a blush, and forcing her brothers to look to quickly marry her off before she is disgraced. With the help of one of her maid's, she manages to dispel the blush with the help of certain herbs, but will they have further effects upon her?

And when the two sisters are torn apart, will either find love? Will the one who goes to live with her sister, now in her dangerous second clutch of eggs, manage to survive in the household of her avaricious brother-in-law, whose culling of weak dragon stock may have more to do with his appetites than his duties?

This is a strange book, but such a thoroughly delightful one. And when I turned from it to Sense and Sensibility, I was wistfully wondering where the dragons were.

4

4

Next up on my series of reviews of books I am rereading is Anne of Windy Poplars, right smack in the middle of the series. It's a weird one to start review the series with, but I've read them all so many times that I know how they fit together.

I've said before that Emily is my favourite Montgomery heroine, and that holds. But that doesn't mean I don't have a huge soft spot for Anne and her life. She is much more domestic in orientation, at least in every book after this one, and that has its appeal. Ordinary life is painted in such vivid and interesting colours that it leaps off the page, putting the lie to the idea that such things are beneath our proper notice.

In this one, Anne is engaged, but her fiance has years to put in on his medical degree before they can be married. So, in her mid-twenties (right? I was trying to do the math, and it's got to be around then), Anne accepts a three-year job as principal and teacher at a high school in Sunnyside. Moving there, she boards at Windy Poplars, living with the two "aunts" and their housekeeper, Rebecca Dew, a tomato-coloured entity in her own right.

When she first arrives, the town is up in arms, because she got the job for which a favoured relative of the local "royal family" had applied. She has to struggle through a first semester while under siege. But does she win them over? Is this Anne Shirley we're talking about?

Anne of Windy Poplars is really a set of connected short stories, linked together by time and place. We watch as Anne befriends her small next-door neighbour, suffering under the none-too-gentle eye of her grandmother and grandmother's servant. We see Anne intervene in several local love stories, with good and bad and sometimes ridiculous results.

She helps her students, tries to befriend a prickly fellow teacher, and generally, becomes beloved by everyone. Which is much less saccharine as it sounds, as Montgomery always has a deft touch and knows just when to stop. People feel real, in all their absurdities, small cruelties and kindnesses.

I have always enjoyed this particular volume quite a lot. It's Anne's last hurrah by herself, before she becomes a wife and mother, and it's interesting watching her negotiate a position of relative power in a way that is all her own.

But I keep coming back to what Montgomery does best. She imbues everyday occurrences with such vivacity that they come to life before our eyes. I can't think of another author who does what she does so well. That these are women's stories that still feel real, decades and decades on, is a real accomplishment.

6

6

There are a lot of catch-22s in the working world. There are even more for women. If you don't ask for a raise, you're less likely to get one. If you ask for a raise, and you're female, it has a real impact on how people perceive you. Be ambitious, but not too ambitious. Be nice, but not too nice. Work your ass off to get ahead, but still find the time to parent. Sheryl Sandberg has done a very good job of bringing together tons of evidence about how women experience the professional world, and some suggestions on how to deal with issues that may arise.

They are practical suggestions. They are good suggestions. And at times, the book still irritated me. For two reasons that I can extract from my hunched shoulders.

1) While talking about the difficulties women face in the working world, she accepts as a given the general corporate workplace culture of constant employee availability that I truly believe is not really good for anyone, male or female. (And as an introvert, parts of the corporate culture outlined in this book gave me quite a bit of anxiety.)

2) While she cites great studies about the double-bind women are often in in the workplace, she supplements this with personal anecdotes that are virtually all about how the men she worked for were incredibly responsive to her concerns when she raised them, and mentored and taught her. The personal experience comes through as universally positive. Which, great. I am so glad that she had those experiences. But when the anecdotes are all positive, they tend to overshadow the studies. And they aren't, to use her language, my truth. It would nice to have some balancing anecdotes about the workplace issues for women we know exist. So sit down for a second, relax, and let me tell you a couple of my stories. Because we can only grow stronger when we share our stories, the bad as well as the good. Unceasing positivity is not all that helpful, particularly when it feels isolating to those who have had bad experiences.

I am not going to slam this book as not really being for the vast majority of women. It's true, and Sandberg fully admits it. It's for women who are attempting to dive in at the deep end of the professional spectrum, particularly, but not exclusively, in the corporate world. That audience compared to the number of women who are just trying to make the ends meet is very small. But there is room for a book aimed at the professional class. I just wish there was a tiny bit more acknowledgement that for many women those career paths are inaccessible not for lack of ambition, but due to lack of resources and class privilege.

(You know, speaking as someone working two part-time jobs while I write on my dissertation, and is going to graduate with a massive student debt that may have a very real impact on how I have to approach my job search post-degree.)

Let's return to the first point. I'm all for ambition. I'm trying to make my way in a profession (or will be, as soon as this bloody dissertation is done) that I truly love, and that I will devote a great deal of my time and attention to. But still, I bristle at the idea that in order to be successful, people have to strive for a work-life balance that includes constant work, even when it's at home. Sandberg talks about carving out family time, but it's in the context of still needing to be available on vacations, in the evenings. I'm sorry, taking a family dinner hour as the only time you aren't available to your workplace fills me with dread. Working only 9-5:30 and then leaving loses some of its gloss when you then work all evening, just in another location. That isn't really limiting your working hours to have some life outside work. That's working in two locations, and I think that needs to be recognized. And fought.

Her life makes me feel panicked to just read about. Which is fine. I was never going to be a high-flying corporate executive anyway. But more to the point, I'm not sure that that should be what the workplace environment should require of people. Of anyone, male or female. I read about the corporate workplace, and what it screams to me is not that this is what it takes to succeed. It screams "these people need to unionize, because this is just fucking unacceptable." It screams a need for collective action, as opposed to individual endeavour.

(Of course, we're mostly talking about the managerial class, and a Silicon Valley ideology of individual endeavour and success, so trust me that I realize unionization is not on the horizon. But this is a corporate culture that can grind people into the ground because they are atomized, because they see their successes and failures as purely on their own terms, as opposed to symptoms of a sick system. It cries out for a realization of community and the ability to collectively change things, rather than just say "this is the way it is, it isn't going to change." Yes, I'm left-wing. Why do you ask?)

Also, can I quibble that an open-concept office floor, with no offices or cubicles, means a non-hierarchical workplace? Bullshit. When you have no space of your own to which you can retreat, that pretty much makes it apparent that time to think and reflect is in no way a corporate value. When you have to worry about whether or not you're looking productive enough every time anyone walks by, that reinforces power structures. It doesn't dispose of them. No walls does not make power disappear. And the energy spent on that could be much more usefully be spent in things other than stress because someone walked behind your desk. I say this as someone who has worked in both open-concept offices and had her own office, and was generally a very hard worker.

And as an introvert, it gives me the heebie-jeebies. I may not have loved everything about Susan Cain's book, but please, please, please, Sheryl Sandberg, read her chapter on open concept offices, and why they are bad for everyone, but will particularly handicap your introvert employees, who have some really awesome things to offer your organization!

Now, after a long digression, off to point number two! As I said, I am very glad Sandberg has had such great examples of men in her corporate lives who have been more oblivious than anything else. Her examples are almost all of men who are willing to change when things are brought to their attention. And we need to keep bringing things to their attention. But, unfortunately, I think that many women don't have that experience, particularly at lower levels of the working world. I wish all bosses, male and female, reacted the way most of Sandberg's colleagues have. But I also think we need to discuss, in detail, the bad examples, so we know we are not alone.

When I taught a course on Women and the Workplace, I was amazed and slightly depressed by how many of my students came to me to tell me of their own experiences in the working world in which they had already experienced discrimination. All these wonderful young women in their early 20s that I hoped would have no idea what I was talking about, they already knew. I was glad I was there to listen. I was particularly thankful that the course was there, through which they could see their own experiences in a larger historical context, and take away some knowledge of how these working conditions developed, and the ways in which they have been fought.

So here are my stories, shared in a hope that by acknowledging them publicly, other women will feel less alone. These do no one any good when they fester, and festering in my mind they have been, particularly one.

When I came back to work at a retail store after a bout of mono, one of the floor managers stopped to ask me how I was feeling. That got her reamed out in front of customers by our big boss for having stopped for a chat.

I have been told that my job was "a good one for a second income" by my boss, who knew full well that mine was my family's only income. Wonder if that had anything with the raise they kept promising me every time I applied for another job, but which never materialized?

I have been told that I had "too much initiative" in a formal performance review, because I would go looking for other work to do when I was done my own work. That did not do wonders for my attachment to that job.

And the big one:

I was working at a university office between my graduate degrees when an Assistant Dean decided that an acceptable way to discipline an entire office-worth of women for not having locked the door (the lock was actually broken) was to stage a burglary, hiding all of our computers in the basement.

When one of the women left the office, extremely upset, and met said Assistant Dean on the street, he told her he was "teaching those girls a lesson."

The next day, when he pulled us all together to ream us out for the door, I stood up and said "Yesterday, I felt threatened. I felt vulnerable. Do you think that is acceptable?"

He said yes.

He said he would have done it to anyone.

The only two of us in the office who were willing to speak up and call him out, or to pursue taking this to the ombudsperson's office were, unsurprisingly, the only two of us who didn't desperately need to keep our jobs. I already had my acceptance to a Ph.D. program in my hot little hand, and she was re-entering the working world after some time away. While she wanted a job, her husband's income meant she didn't need to keep this particular job.

This is not a coincidence. This is how power works to silence people. When you are scared for your job, you don't speak up. I don't fault the women who didn't. I do fault the fucker who put us in that position in the first place and then refused to admit he'd done anything wrong.

By the time the school took this seriously and brought in someone to look into it, the other woman and I had moved on. My friends who were still there told me that they felt pressure in the interview to minimize what had happened, and to downplay the impact it had had on their emotional and workplace wellbeing.

When the report came out, it was summarized to me by one of my former co-workers as "those women need to learn how to take a joke."

And no one was left to make a fuss.

This happened almost ten years ago, and yet it still makes me shake to remember it. I remember being terrified when we thought we'd been robbed and didn't know if a burglar was still in the building. I remember shaking when we found out what had happened. I remember shaking when I stood up to ask my question, and being aghast when I got my answer. I remember days of not sleeping, and such anger. It's not a subject about which I am particularly polite, but this incident has come, in my mind, to symbolize what a sick workplace culture can look like.

And that's my truth.

I hope women find help in Sandberg's book. I found some very helpful specific advice. But it is also part of a corporate culture that fills me with dread. But I do think we need to share our stories, as women, as workers, as part of this world. It's the first step to changing it. I'm glad Sandberg shared hers. And here are some of mine.

This is a strange little book, and far from Bester's best. But it was nominated for a Hugo, and so I read it, and it's weird. With some redeeming moments. And a lot of vaguely uncomfortable but yet vaguely progressive gender and racial politics. I don't quite know how to wrap my head around it. I guess that's what this review is here to do.

There is a lot going on here, and for the first half of the book, it's fairly confusing. Let's see if I can break it down. I don't think I'm spoiling anything if I tell you this book is about a bunch of theoretical immortals. That's in the first chapter. There's a "scientific" reason for this, something to do with cleansing out all the bodily toxins when you are in pain and about to die and have accepted the inevitability of death. You also maybe have to be epileptic.

Those who have passed through that crucible are immune to aging, drowning, most diseases, although their condition carries its own looming death sentence if they're not careful. Each member of the Group names themselves after a major historical figure they identify with, except Jacy, who actually is a major historical figure.

One, who calls himself the Grand Guignol, is trying to make more of their kind - tracking down potential candidates, and trying to kill them in just the right way that they might achieve eternal life. He's not that successful, so far, and an interesting choice for a main character. But he has unexpected success with a Native American (this book was written in the 1970s, so yes, it's "Indian" all the way through) scientist, Sequoya. But for reasons that aren't entirely convincing, a seizure when an experiment goes weirdly awry, means that Extro, a huge computer network, infiltrates Sequoya's brain.

So we have a group of immortals, one of whom is possessed by a malevolent computer. And there may be other things behind the scenes. This is then a cat-and-mouse story, as the Group tries to track down the scientist and the computer, without tipping their hands to either. Along the way, Guignol gets married to the scientist's sister, and there are strangely problematic statements on squaws. But on the other hand, Native Americans are easily half the cast in this one, and range from scientists to politicians. It's a weird mix that perhaps only the 1970s could produce.

So it's a race around the planet, trying to stay off the grid in an increasingly computerized world (sound familiar?). The Computer Connection is such a weird mishmash of things that didn't quite achieve the status of a satisfying book, but parts of it are great, and other parts intriguing, and if I'm left with the feeling that the parts are greater than their sum, well, not every book is a classic. Bester will have to be satisfied with the two genuinely deserving classics he wrote.

5

5

Dark Currents is better than the first book in the series, which struck me as okay, but weak. But it isn't a lot better. The Emperor's Edge was interesting enough to make me this self-published author a second chance, but while this does represent a step forward, it's not enough of one to make me enthused about the series. And so, I think we're going to part ways here. There isn't anything I'm hanging fire on finding out, so while I find them moderately amusing, I think I'm good. There are a lot of books out there. I feel I've given these a fair shake.

These are the continued adventures of the Starship Enterpr, er, Amaranthe, former city enforcer, and her motley crew of mercenaries/compatriots/vigilantes/do-gooders. Yeah, that's a little messy. And so is this, honestly. We're still in the fantasy/steampunk world, with a huge emphasis on the businessworld of this kingdom of...oh damn. I don't remember the name of the Empire. Whoops.

Both books have focused around businesspeople and their negotiating of imperial economic legislation, including tariffs and restrictions on foreign-owned businesses. It isn't that the roots of those ideas aren't interesting, but they're largely kept at the theoretical level, instead being connected viscerally to the characters.

Yes, there is a foreign businessperson being forced out of business, but it's more background dressing than anything else. So, why the subplot about the emperor's economic policy? The book is actually about a threat to the main city's water supply, by local businesspeople and foreign shamans, intent on poisoning the water (literally) so that the city will be forced to turn to another source that, coincidentally, they own.

Amaranthe and her crew are intent on stopping it, as part of their ongoing efforts to do good in the city and come to the attention of the Emperor, who will then fold them into his fond embrace. That's the plan, anyway. She has a master assassin, a bookish teacher, a male model sword-wielder, a street rat/magician and a former slave. And the supporting cast are okay, but again, it lacks the exxtra level that would really grab me.

And that's what the problem is here. It's not that anything is particularly wrong, there's just not enough right. The writing is okay. The plot is okay. The characters are okay. But okay isn't good enough. One of the three needs to rise to a different level, and although Dark Currents is a bit better, it's still not enough for me.

If you're looking for a fun fantasy that doesn't really add anything new, this is not the worst way you could spend your dollars. Maybe they get a ton better, and I do see improvement between the first and second books. Hopefully she continues to develop her chops. But I think I'm done.

This is only one step elevated from being what I call an "issue" book, as the characters seem to be slightly more than profiles taken from the textbooks devoted to the issue, given names and bodies, and little else. On the other hand, in order to emphasize most thoroughly the impact of the medical condition she's chosen to explore, Genova has given us a main character is who is almost unbearably annoying.

So I'm a bit ambivalent about this one, when it comes right down to it. Chalk this up as another in the long list of "it was okay."

The "issue" at hand is Left Neglected Syndrome, a condition that sometimes happens, says the author, (and I'm not spending the time fact-checking her,) after strokes or brain injuries, where the brain forgets that the left side exists. It's still there, and can be moved, with rehabilitation, but the brain forgets there ever was a left.

Sarah is a high-powered executive juggling three children, a marriage, and a job that eats all her time and then some. Naturally, she multitasks even when driving, and unsurprisingly, that means she gets into a car accident. She wakes up in a hospital, and has developed the above syndrome.

In a plot that seems entirely predictable, this former workaholic has to learn how to appreciate the little things, slow down, and accept that her life has changed. Because, presumably, we need conflict, she is the brattiest possible person about doing so. Throw in an estranged mother who Sarah rejects when she comes to help, and we have a paint by numbers book of the aftermath of a brain injury.

It feels like I'm being overly harsh on a book that, was, truly, not that bad. It's just not surprising or challenging, either. If you want to pretty much know what you're going to get by reading the flyleaf, this'll be fine. But there isn't anything deeper or more challenging than that. I'm glad that Sarah stopped being whiny and learned to celebrate the slower pace of a more difficult life. But is that it? Really?

Now I feel like I've just kicked a puppy, because after all, this is exactly what some people are looking for - unchallenging escapist fiction. And if that's your thing, this is a good crack at it. I'm not saying there isn't a place for that. But this isn't the escapist fiction I would choose, and while I didn't hate reading it, that main character was obnoxious enough to make it difficult to pick up sometimes.

If you love this author, please take this all with a grain of salt. The book is fine. It's just not my cup of tea.

Wow, this is the wrong morning to try to review a light-hearted book. I'm sleep deprived, stressed about family issues, and about to cry if someone so much as looks at me sideways. I contemplated putting this review to the side and writing it later. Fuck it. Let's see how it goes.

It's almost too bad I read this before the present moment, because this is exactly the type of book I like to settle down with when I'm stressed. It's entertaining, it isn't too taxing, and it might make me smile. The characters are likeable, the plot interesting, and if it didn't make me tense, well, there are times when that's just what I need. Like today, for instance.

I didn't find it that funny, though. Given the cover blurbs promising hilarity, I feel like I ran smack into my issues with finding American comic fiction not that funny. Amusing, yes. Absolutely. But I don't think I even giggled during this one, although there were the occasional smiles. It might be me. But there it is.

This is, of course, a riff on the joke about being absolutely screwed if you're wearing a red shirt and are on a Star Trek set. But this is real life! Or is it? I enjoyed the meta-ness of this novel, the idea of narrative influencing actions across divides otherwise impenetrable.

The main characters are five new redshirts on a spaceship with an alarmingly high death rate. Much higher than any other ship in the fleet. And arguments that they're the flagship, and do more adventurous stuff, hence the death rate? Don't wash. (But one of the main characters is a scientist. Shouldn't he be a yellowshirt, technically?) They come into a ship where people avoid the commanding officers like the plague, because being picked to be on the away team is the same as a death sentence.

In fact, this is so extensive that warning systems have been put into place, as the new crewmates discover when they are suddenly deserted by a room full of compatriots who are mysteriously gone for coffee (or hiding in a storage closet) when the commanding officers stroll by. And when on away missions, the doomed redshirts seem to find themselves under a compulsion to act in just exactly the way that is going to end up in a dramatic death. And don't even mention the poor lead Lieutenant who pays for his handsomeness by almost but not quite dying multiple times a month.

There is a nice wink to the metaness of the metaness near the end, after the redshirts have launched a desperate attempt to convince The Powers That Be to change the narrative. (I can't be any more specific without giving so many spoilers I don't think I could post this.)

While I enjoyed the novel, though, two out of the three codas felt superfluous. I liked the first, and the questions it posed, although I think those questions were implicit in the story as a whole, and I'm not entirely convinced I needed my hand held through them. But still, it was entertaining. The second and third, though, are even more hand-holding, and it starts to grate. It feels like Scalzi doesn't entirely trust the reader here, and has to make sure they're taking the message exactly the way he saw it. It's not that they're bad messages, they're just a bit anvilicious. I would have a preferred a bit more trust in the readers to finish it off.

But all in all, it's an entertaining read. It would have been just the thing today. Too bad nothing on my current docket fits the bill quite as well as this would have.

There was a much larger gap between reading the first and second books in the Eddie LaCrosse series than appears on my blog. I only recently moved over the review from the first from Goodreads, although I wrote it months ago. And the second book came around on my friend's Kindle (yes, I still have it - let me know if you want it back!). So in reality, there was a large gap, although to the Internet it doesn't look like it.

But that's only for people who are worrisomely interested in my reading habits. What about the book? I'm happy to report that the second entry into this fantasy noir series is just as much fun as the first. I can't say that it's mind-boggling, but I was always eager to pick it up and read a few pages more. It's entertaining and light and the world Bledsoe has created is a new take on an old genre.

Eddie LaCrosse is still up to his old tricks as a sword swinger for hire. But as he travels home one night, a bruised and bloodied young woman stumbles out of the woods right in front of his horse. When he tries to get her back to town, they are both captured, and he wakes up at the bottom of a cliff, dropped there by people who presumed it would kill him.

Well, when someone kills someone you'd taken under your protection, no good sword jockey could let it go. Soon he is plunged into a world of underworld bosses, dragon worshippers, absentee heirs to the throne, and the fact that his lover appears to be lying to him. What's an honest guy supposed to do? Particularly when he keeps getting the shit beaten out of him?

Imperial investigators are also sniffing around suspiciously, and the stables of a friend burn down mysteriously. With the friend inside. The body count rises. And there are stories of dragons flying overhead. Eddie scoffs.

These books are fun and enjoyable, and Eddie an appealing hero.

But that's a small matter compared to how much enjoyment I have gotten out of the first two books in the series. I look forward to the second, although there will be another pause before I get there. I don't know that I'd want to chug these books. But sipping them every once in a while seems just about right.

6

6

I have to say, I still enjoy these. I don't know that they are as shiny and new as when Jasper Fforde was a discovery, but I do enjoy them. I felt like the one before this was a bit muddy, if I remember correctly (it was a while ago), but First Among Sequels is a thoroughly fun addition to the Thursday Next series. I really never get tired of Fforde's voice. That's what it comes down to, in the end.

In this one, we jump forward more than 10 years, to a point where Thursday is still working for Jurisfiction, but her position in the real world is, ostensibly, carpet fitter. At least, that's what her husband thinks she does. And the cover office does seem to be doing a roaring business. You know, in between killing vampires and solving literary crimes. Of which there are fewer and fewer, as books go unread, under the spectre of reality TV. And then the horrific prospect of book-based reality TV that will change literary classics forever! Ghastly!

Meanwhile, her son Friday is steadfastly refusing to grow up into a responsible young man who will head the ChronoGuard, and is instead sleeping in till the afternoon, refusing to cut his hair, and playing rock music. Since the end of time is fast approaching, the ChronoGuard is understandably concerned about this.

And Goliath Corporation is being strangely helpful. That can't be good.

In the middle of all this, Thursday Next is training two new Jurisfiction candidates - Thursday Next and Thursday Next. Thursday Next 1-4 comes from the previous four books, and those books, this time, are rife with attitude and guns. Thursday5 is from the completely unread fifth book, an attempt to course correct that ended up with a New Age attitude and an obsession with being nice. Our Thursday isn't too happy about any of them.

And the little tweaks to classic literature, changing thing to the way I know them, such as the piano in Emma still crop up every once in a while, and they're delightful. There is also a visit to the sea of Moral Dilemmas and another Minotaur attack.

Underlying the whole book are the twin worries of people not reading anymore, and the emphasis on the near future. Both the worries of the literary world and the ChronoGuard turn out to be intertwined, and Thursday must help try to find a way to get back a Longer Now than her world currently embraces.

It has all the love for and irreverence towards literature that I've always loved about these books. It's not quite as fresh as when I first read it, but this is a fun entry into the series.

4

4

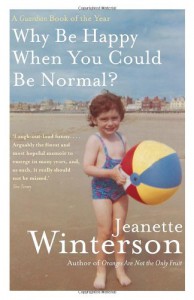

When a memoir starts with a title like that, it's apparent it's not going to be all sweetness and light. Particularly when it's fairly quickly on the table that it is Jeanette Winterson's adoptive mother who said the titular line. With that established, this is obviously not a slight read, slim though the book may be. But more importantly, I felt like it was interesting but not anything more than a fairly straightforward memoir until about halfway through - and then the book was elevated to another level, became something rawer and truer and tougher and more emotional than I had seen so far. It was like the first half was the backstory we needed to understand the second half, but the second half was the book.

And that tells you pretty much nothing at all. So, in a fairly straightforward linear fashion that will capture nothing of the flavour, the book is about Jeanette Winterson's experiences growing up in a household where she had been adopted by a Pentecostal couple. Her adoptive mother was deeply troubled, prone to depression and anxiety, and who definitely never understood her adopted child. Winterson found solace in books, and we'll come back to that in a minute. She finally moves away/is thrown out of the house over her relationships with other girls her age, and, in an extreme long shot, is accepted at Oxford.

The book then jumps forward decades to a point where a relationship has ended, and she sinks into a psychiatric crisis, detailing her experiences through it in terms amazingly stark and poetic at the same time. This goes hand in hand with her journey with her new partner to discover her birth mother, the agonizing process to do so, and the complexity of those meetings when they eventually occur.

And this second half is where the book takes flight. While the early years are interesting, something happens to her prose when she is talking about her bouts of madness, her efforts to put herself back together, to heal a self that was fractured shortly after birth. I really can't explain it, but it's something you should experience.

There are two themes I want to explore more fully. The first is the lifeline that she found literature to be. Winterson is eloquent in combatting the notion that literature is elitist, that it is somehow only for the rich, and not the poor, and that it doesn't matter if the poor have access to good books, that good books are irrelevant to their existence. She makes a strong case that she would not have survived without her access to a library and her juvenile attempt to read all of "literature," A-Z. Coming from a very working-class home, Winterson is, and I am, infuriated by the notion that reading is the sole preserve of the rich.

The other theme is the need for more complex narratives of adoption and reunion than the joyful, tearful, uncomplicated one that seems to permeate our culture. Winterson makes that call directly, and I think it is an important one. When the narrative is that finding a birth mother or father is the end of struggle, of pain, and the start of an uncomplicated relationship, that does a disservice to everyone who does not find it to be so. They are left out of the literature, left out of the representation, and will find no reflection for themselves. And for people already searching for a sense of heritage, simplistic narratives do no one any good. Winterson's efforts to find her birth mother were difficult, and the new relationship hard to navigate.

I had never read any Jeanette Winterson books before this, although I did and do intend to get to them. This memoir is an interesting way of being introduced to her work, and the second half of it convinced me I need to search out her work sooner rather than later.

10

10

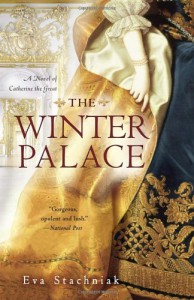

This is the other historical fiction I was reading while I was reading Wolf Hall, and musing about my reactions to both. I would still say that Wolf Hall is a step above most historical fiction I've ever read, but this wasn't bad. It wasn't earth-shattering, either. But not bad.

The Winter Palace is about a young woman employed by the Empress Elizabeth of Russia as a spy on the rest of the court, (officially, a lady-in-waiting, of a sort). But she becomes friends with the future Catherine the Great, and turns coat to report to Catherine as well, particularly when Catherine seems to be isolated and alone.

Wow, I seem to have run out of things to say fairly early in this review. Why is that?

I think it's because, while The Winter Palace is a fun read, there's little that sticks with me. Normally, I'm bursting with themes, or characters, or ideas, or moments to explore, either good or bad. In this case, very little sticks out. Varvara, the main character, never really won my affection, but she never alienated it either. I guess, in the end, I don't really care about her that much.

Oof. That's a problem. I hadn't really been fully cognizant of how little the book struck me. It was a pleasant read, but there is so little more. The court politics in the book are fine, but not that acute. In fact, many of the emotions seem muted, even the ones surrounding children being taken away. There is one good crying jag, and then a lot of bitterness - but the bitterness itself seems washed out and distant instead of burning. The book talks about grand passions, but I felt little of them. Possibly because they were supposed to be of the characters Varvara was watching, but mostly from a distance.

And the crux of the betrayal at the end seems slight.

(show spoiler)

I couldn't tell you why that is, though. Stachniak certainly shows us the repercussions for one other discovered spy, but there's no real sense of danger around Varvara. She seems to skillful at what she does, and the suspense is not effectively communicated. There's just something lacking here, a real sense of urgency and the ability to make emotions keenly felt.

I think this is an issue of the writing, which is otherwise quite competent. It just needs that extra edge to make this story compelling. As it is, it's an enjoyable read, but very little of it really distinguishes itself for me.

6

6

It's odd that, in trying to figure out how to explain this book, I first have to figure out exactly what is the sexually transmitted disease. It's not citizenship in the strange city of Palimpsest - that has to be earned. It's not passage to the city, as that has to be achieved, every time someone goes. It's the passport, I guess. The black markings of the city streets on the skin that never leave, that mark a person as someone who could go to Palimpsest, if they choose. Tattoo as sexually transmitted disease (okay, fine: infection. I know it's supposed to be infection these days. I just grew up with STD as the acronym and am having trouble switching to STI.)

And if that preceding paragraph isn't enough to tell you that this is a little bit unlike anything you've probably read before, I don't know what would. This is a strange and delightful little fantasy, about one of those cities that exist somehow alongside our own reality, accessible through mysterious means. Think Neverwhere, or Un Lun Dun. But passage to Palimpsest used to be easier, and being able to stay something achievable. A civil war was fought over immigration, and the repercussions are still being felt. (This is a slowly developing line through the book, unfolded as the main characters discover it.)

The mechanics are strange, but I think the important part is how much depends on someone else. You can't get there alone. You acquire your map to Palimpsest through sexual contact, and for each person, it turns up on a different part of your body, and on each map, a different intersection is highlighted. To get back, you have sex with someone else with a map, and each of you goes through to the spot on the other person's map. (I'm a little fuzzy about exactly when. Doesn't seem to be at the moment of orgasm. When you sleep afterwards? What if you don't sleep? One character had time enough after sex to take measures that meant she wouldn't remember her visit.)

But it's the interconnectedness. Your journeys are dependent on another person, and having that be sexual adds another layer of complexity to the story. And that's one of the things I like best about Palimpsest. Sex isn't a punchline. It's integral to the story, but it isn't there for laughs. And such a variety of sexual experience! Not just orientations, but multiple partners, sex as a sacrament, sex as a duty, sex as a rote exercise, sex for fun, sex for pain, sex to heal. So many ways people could use sex, taken seriously. How rare is that?

The story centres around four potential immigrants to Palimpsest, each marked after an initial sexual encounter. Amaya Sei, a young Japanese woman with blue hair, obsessed with trains, and carrying deep scars from her life with her mother. Oleg, a Russian expat living in Brooklyn, haunted by the drowned ghost of his sister. November, a solitary beekeeper from northern California, maker of lists. Ludo, Italian bookbinder whose wife has drawn away from him to her own group of four from Palimpsest. Their stories intertwine, slowly, leading to a quest to find each other. The citizens of Palimpsest remain divided on the treaty on immigration that ended the war. All four pay a price, and not all prices are acknowledged.

I love, as always, Valente's prose. It's beautiful, and in this case, weaves around you like the city itself. It's such a joy to read someone so skillful with painting pictures with words, sumptuous, incisive, and apt. I don't know if I want to immigrate to Palimpsest, let alone get my mark. But I enjoyed the visit.

10

10

With this review, we're revisiting another one of my old favourite, my comfort reads, the books I can still pick up and read with a great deal of pleasure, almost as much as when I was curled up in my bed as a girl, discovering this world for the first time. Which is all to say that this review is naturally heavily coloured by all of who I was and who I am now, and how this book has fit into my personal mythology for many, many years.

I always loved the Emily books far more than the Anne books, and that's saying a lot, because I also have a huge soft spot for Montgomery's best known creation. But Emily gave me more scope for imagination, as Anne herself might say. Her adventures were a little less domestic (although still quite domestic), and the slight touch of the supernatural that insinuates itself at least once in each Emily book is intriguing.

Emily has more ambition than Anne. Reading about Anne as she throws herself entirely into her role of wife and mother is interesting, but Emily's disdain of that path, her ambition to really become a writer, to put her own desires above those of her aunts, they were all very appealing to me when I was young, and even now as I'm in my late 30s.

Emily is, as most Montgomery heroines are, an orphan. But she is not cast to the winds, she is taken in by her mother's family, and although Aunt Elizabeth may be stern, Emily is thoroughly loved by Aunt Laura and Cousin Jimmy. When she moves to New Moon, she finds a home, makes one, populates it with the friends she finds, and thoroughly enjoys life there, while still missing her recently-deceased father.

In the first book, we are mostly covering Emily's adventures as a young girl, which are full of thrills and adventure that may lack in genuine danger (well, most of them), but can spur genuine fear. Emily is a sensitive little creature, and her voyages through her own world are delightful. Montgomery had a knack for making everyday life sparkle, of capturing small details and investing them with significance and beauty.

The social historian in me loves how she pays such attention to everyday life, to the small victories and defeats that nonetheless loom large in the eyes of those who participate in them. There is such richness here, and it is rarely equalled by other authors. And Emily herself is one of my favourite literary friends.

Two volumes in. One third of the way through this extremely long work, or series, or whatever it is. And it's hard to pinpoint what exactly it is that's keeping me interested. I am, but it's hard to say why. It's not the plot - there is barely any. It's in translation, so I'm sure I'm missing some of the nuance of the original. It's not so much the characters - other than the main one, the others are mostly sketches, and the main character is self-absorbed to the point of being irritating.

And yet.

There is something here, a richness of prose, a capturing of small moments, a lingering on the everyday that is exquisite. He describes moments I recognize but have never seen in prose. He describes moments far outside my experience. And deftly, weaves them all into the tapestry of a life. Even if it isn't an exciting life, or so far, a particularly productive one. There is the feeling here that all lives are worthy of notice, no experience too evanescent or frivolous or fleeting to evade his pen.

So far, however, the narrator is a very self-absorbed young man. Within a Budding Grove chronicles his love for Gilberte, the daughter of Swann and Swann's wife, Odette, a former kept woman turned wife, whose past keeps her from the best society. And then, after that relationship has soured, it turns to his stay on the seashore, and his subsequent attraction to Albertine.

But it's mostly about the narrator. It's interesting, his insistence on being sensitive, and yet how far away that is from my own experience of being sensitive. For him, it takes the form of an almost total self-absorption, a fixation on his own body and his own emotions. While I can't plead innocence from thinking about myself, my experience has been more weighted towards an oversensitivity to the emotions of those around me, which is not what the narrator here experiences. In fact, he often assumes things about the people he's talking about based on his own expectations which the narration undercuts.

It's a strange mixture of callow and oversensitive. And he blunders around, not being a very good friend, being too obvious as a suitor, missing many of the social nuances around him, which he, as a narrator, shakes his head over ruefully, obviously looking back from a distance and wincing at the overeagerness of his youth. If the character verges on irritating, the narrator, who is and is not the same person, puts it all into context that makes it more bearable.

There are also a lot of interesting bits in here about class consciousness, nobility and merchant class, and the ways in which each mistakes the perceptions of the other, expecting them to be the same as their own. So the middle-class dismisses the conscious simplicity of dress of the aristocracy as a sign of poverty, while the aristocrats assume the middle-class knows exactly who they are and are paying them all due homage.

I feel like I've done an inadequate job of capturing this book, and the greater work as a whole. But it's hard to get a grasp on. And I'm enjoying my leisurely trek through its pages.

1

1